“Congo red is the essential histologic stain for demonstrating the presence of amyloidosis in fixed tissues. To the best of my knowledge, nothing has been written about why the stain is named ‘Congo.’ ” according to Dr. David P. Steensma.

So how did this stain get its name? Where did it come from, and does it have a connection to the African Congo? The history is fascinating and below, with Dr. Steensma’s permission, we adapt his story of the history of Congo red.

Congo red didn’t start its life as a histological stain nor was it initially named “Congo.” Like Prussian Blue, it was developed to dye clothes. In 1857, William H. Perkin in the UK created the first synthetic aniline dye, a purple color he called mauvine, later known as “mauve.”

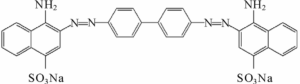

Until that time, mostly natural dyes had been used to dye fabrics. After Perkin’s discovery, there was a race to create synthetic colors – mostly in Germany, mostly aniline dyes. This is the chemical structure of Congo red; aniline is a phenyl group attached to an amino group.

A major problem with older fabric dyes is that they wash out easily. To stop fading, another chemical, a mordant, is needed. Companies in the late 19th century were keen to find dyes that didn’t require a mordant, to save time and money. (A company in Connecticut sells this one.)

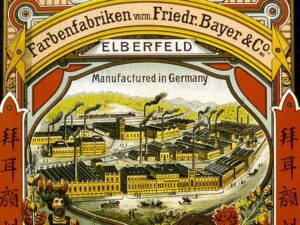

In 1883, a young German chemist, Paul Böttinger created a new bright-red dye that stained fibres without needing a mordant. He brought it to the attention of his bosses at The Friedrich Bayer Company but they weren’t interested. Reportedly they were looking for a purple, not red.

So Böttinger left Bayer and patented the chemical on his own. He offered it to several other companies, but they weren’t interested. Finally, a small Berlin-based dye manufacturing company called Agfa (Aktiengesellschaft für Anilinfabrikation), founded in 1867, bought it.

Congo red was a huge commercial success for Agfa – so much so that many other aniline dye companies went out of business. Bayer, the company that rejected Böttinger, only survived by creating their own Congo red … Agfa then sued them. (Clever sticker is from a Medium blog post.)

It became a classic case in patent law. The “non-obvious” clause in patent world comes from Congo red. Agfa and Bayer decided the lawsuit was becoming too expensive so they settled, agreed to co-market Congo red & share the profits. (This image is from http://chm.bris.ac.uk/motm/congo-red/congo-redh.htm…)

The lawsuits & lost sales had almost bankrupted Bayer. But now, with money from Congo red sales, Bayer was able to hire new chemists. In 1898 Bayer marketed heroin (!), and in 1899 they marketed a new drug you’ve probably heard of: aspirin. Heroin and aspirin saved the company.

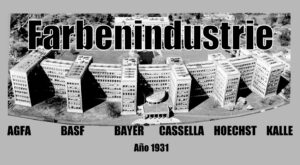

In 1925 Bayer and Agfa and four other chemical companies merged to form IG Farben (Farben = colors/dyes in German). IG Farben made helpful chemicals like dyes and medicines, but also some terrible chemicals, like the infamous Zyklon B. As a result, they were dissolved after World War II.

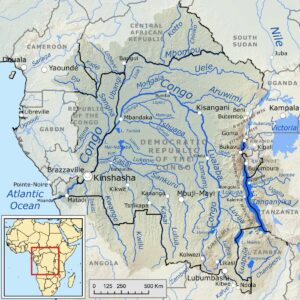

The month Congo red was patented in 1885, there was a big event going on in Berlin: the Berlin West Africa Conference. In simple terms, the European powers were dividing colonial Africa. Otto von Bismarck, chancellor of the newly unified Germany, presided over the conference.

Britain & France already had established colonies; Italy controlled parts of East Africa, Portugal controlled Mozambique & Angola. The Congo basin was a sticking point everyone was talking about. Some “genius” marketer at Bayer thought: what better name to give our new vivid dye?

Other dyes created at about the same time were Sudan Black, Sudan Red, Coomassie Blue, and Bismarck Brown – notice a theme? Africa = exotic and colorful in the late 19th century European mind. Incidentally, Sudan Black is also still used for histology, and Coomassie Blue in SDS-PAGE.

The real-world Congo was in the end given to the Belgian king, Leopold, as his private fiefdom. It became the site of some of the worst atrocities in human history, immortalized in Joseph Conrad’s book “Heart of Darkness”.

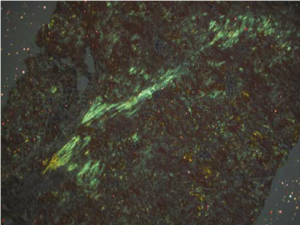

Anyway, Congo red, like many other aniline dyes, immediately started being used for histology. But it wasn’t particularly useful until 1922 when a young German pathologist, Hans Herman Bennhold, discovered it binds to amyloid. In 1929, Paul Divry, a Belgian neuropathologist studying degenerative changes in aging brains, first noted the characteristic green birefringence of amyloid substance when stained with Congo red and viewed under polarized light. (This image is from Lai et al 2007 Kidney Int’l.)

General Principle of the Stain

According to Bitesize Bio,

Amyloid is similar in structure to cellulose, therefore it behaves similarly in its chemical reactions. It is a linear molecule, which allows azo and amine groups of the dye to form hydrogen bonds with similar hydroxyl radicals of the amyloid.

When examined in haematoxylin and eosin-stained sections of tissue, amyloid appears as an amorphous, glassy, eosinophilic material. Since this can be confused with some other materials, Congo red staining is needed to identify it.

When examined using regular bright-field microscopy, Congo red-stained amyloid appears pale orange-red. However, the bright field appearance alone is not diagnostic for amyloid, because small deposits may be difficult to see. Congo red-stained tissue sections must therefore be examined under polarised light allowing the characteristic ‘apple green’ birefringence to be seen which is diagnostic for the presence of amyloid.

Conclusion

Dr. Steensma writes “Congo red began its life as an extremely valuable textile dye – a dye of such importance that it not only revolutionized the textile industry but also resulted in a patent challenge that changed intellectual property law.” Decades later, the Congo red histologic stain is the gold standard today for the demonstration of amyloid in tissue sections.

Imagine that.

———————————-

Many thanks to Dr. Steensma for his permission to share this interesting story.

Reference:

“Congo” Red by David P. Steensma, MD; Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, 2001